Week 71 - Egypt Part 2

Continuing our adventures in Egypt, tombs and temples in Luxor… A break from our adventures in Greece cruising the Mediterranean on our…

Continuing our adventures in Egypt, tombs and temples in Luxor… A break from our adventures in Greece cruising the Mediterranean on our boat Matilda.

WARNING: This week contains a lot of “Tim’s version of Egyptian history” which is at times apocryphal, overly simplified and just plain wrong, but in my defence, when you’re trying to make sense of around 2800 years worth of monuments, the occasional short cut is in order. I hope you find it entertaining and educational.

Egypt is really old. To put things in perspective, if you consider Cleopatra VII — the “last active ruler styled as a Pharoah” (more on her and this later), she died in 30BCE, which puts her 2051 years ago. The largest (and first) of the “Great Pyramids” at Giza, completed construction around 2,650BCE, which means it was built 2,620 years BEFORE Cleopatra VII’s time. We’re closer to Cleopatra than she was to the great pyramids.

The history of the Pharaohs covers roughly three “kingdoms”. The “Old”, “Middle” and “New”. General consensus seems to be that these were the periods of time where Egypt (and specifically Upper and Lower Egypt) was ‘more or less’ united under a common ruler. Between these were the “Intermediary” periods where central control had collapsed and the two halves split apart and were ruled under competing leaders, or just local rulers until someone pulled the whole thing back together.

Each of those kingdoms lasted around 500 years, give or take a few years. There was about 170 different Egyptian Pharoahs, ranging from Pepi II who reigned for over 64 years (still not as long as Queen Elizabeth II!), and Tutankhamun who ruled from aged 9 for about 9 years. And all of them (notably excepting Tutankhamun who died too young), were building monuments, temples, tombs and generally trying to set themselves up for the afterlife. They left a LOT of stuff behind in the desert and much of it — particularly from the wealthy and prosperous Middle Kingdom — is centred around Luxor.

The challenge with a location like this is that it’s so full of “wow” moments that after a few hours, you feel like your mind is exploding with information and it’s a struggle to make sense of it all beyond a feeling of “I saw some cool shit”. That’s what I love about slow(er) travel. Spending a week here meant that we’ve had some time to soak it in, talk with people and observe and I think start to unravel it more. For me personally, it’s the small details which make it really fascinating and turns this overwhelming weight of history into something more intimate on a human scale — age old themes like jealously, power and religion and a need to scream into the ages “I was here”.

Our two days in the weird and wonderful world of Russian and German tourist central at Hurghada was fun, but come Sunday morning we were very happy to get on the road again. We had contacted our Airbnb host in Luxor, who arranged a driver to come and pick us up. Mahmoud, who would drive us several times this week, arrived on time in a brand new white Kia, a welcome luxury after the crappy van with uncomfortable seats that took us from Cairo.

Travel in Egypt is different. You’re not just allowed to drive wherever you want. There are frequent police checks and you have to have a reason to be going somewhere. But for this first part of our journey from Hurghada to Luxor it was straight forward enough. We lucked out (an enthusiastic round of “hamdulillah” from us all) crossing to the West Bank when the guards just waved us by. “It would take an extra hour from here if they forced us to go the East bank” explained Mahmoud.

Our Airbnb is a lovely apartment on the West Bank, with a view out over the rice and corn fields to the west, with the sunset and the hills with the Valley of the Kings, while to the east we have access to a balcony that gets great sun in the morning and a rooftop which gives us a view over the Nile. This is Egypt on a more peaceful and friendly scale. If we have one complaint, it’s the same as all the Egyptians which is that there’s no heating in the apartment and with the temperature dropping from around 20C in the day to 5C — 8C at night, it gets pretty cold!

It’s much more intimate — we’re in a small pocket with only 30 or so buildings along the Nile, which means that every body gets to know you quickly. On the one hand it reduces the hassle; for the most part people try to sell us something once or twice then once they know we have no interest, they leave us alone. Occasionally it turns into a running joke, with one guy insisting that maybe “tomorrow” we’ll take that felucca ride. Of course on the other hand nothing goes unnoticed, at least twice people have said “I know you, you’re staying on the West Bank”.

There are still scams around (notably what people try to charge to cross the river), but we’ve also quickly worked out what the “going rate” seems to be for most things and we’re happy to stick to our guns. It’s tough — life here is hard, inflation on some items has gone up 600% in the last few years and a series of events (Revolution, Economic Collapse and now COVID) have left people desperate for money. But at the same time, you can only take so many rides, use so many taxis or just have no desire to buy whatever it is that they are selling. We try to find a happy medium where we pay more than a local, but at the same time, not a complete rip off either.

On Monday we really wanted to focus on orienting ourselves, as noted prior there is a lot of old stuff to see, but we also want to take in the culture, eat local, shop local and generally feel life here a little (and yes, retreat the comfort of our apartment at night). There’s a lesson we learnt many years ago travelling which is to ask “how do the locals do it”. For example, when crossing the Nile from the East to the West Bank you can go bundled in a tour or take a private motor boat (they’ll start trying to price it around 300 EGP, but typically end up at 30 EGP for one way for both of us) but even at that price it’s really too expensive for most of the locals. It turns out that the typical way they do it is either on the local Ferry (which is about 1–2 EGP for them, we get charged 5 EGP), or there’s a dock where the private boats run back and forward and charge about 5 EGP a head (much faster).

We walked through the village to visit the “Collosi of Memnon”, 18 metre high statues dated to about 1350BCE are what remains of the Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III. It’s one of the few sites you can visit for free and while there are not a lot of remains to see, we found the active excavations and documentation displays on the restoration process to be quite educational. Here’s where we get into “Tim’s version of Egyptian History” — the Mortuary Temples were essentially a Pharaohs version of the “Presidential Library”. A place in proximity to their burial site that recorded the great deeds of their life and where worshippers could gather to worship. It’s worth noting that the Pharaohs were treated as literal Gods on earth, so having worshippers is a natural extension of this — in this regard not much has changed in 3000+ years, many politicians would like you to believe that, if not Gods, that they are divinely guided.

Walking to the Collosi involved walking along a busy road, but it once we were through the village it was also quite scenic as it passed through a lot of fields. We were fascinated to see tomatoes being sliced up and placed on salt to sun dry them. A little later walking near our apartment, we passed a man who said “I saw you walking on the road near the tomatoes” and proceeded to explain a bit more about it — apparently that facility is run by a German company and all the sun dried tomatoes are exported to Germany.

In the afternoon we crossed the Nile for the first time to the East Bank — the land of the living. The Ancient Egyptians believed that the West Bank of the Nile (where the sun sets) was the land of the dead. It was here that they built all their tombs and mortuary temples. The East Bank was the land of the living and the temples on this side were intended for daily worship of the gods, particularly those focussed on life.

We wandered around to get a feel for various locations, fended off countless horse and carriage operators and eventually headed into the Winter Palace hotel. One of the oldest hotels in Luxor, it was on the steps of this hotel that Howard Carter announced his discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen. We were on the hunt for a Christmas lunch to make a booking, trying to find somewhere to celebrate our upcoming Christmas Day. Unfortunately the Winter Palace was both spectacular AND very pricey! But we enjoyed touring their gardens and the lobby of the hotel.

After this we cruised the local markets, battled through the touts and made our way back home to the West Bank where we watched the sunset over the mountains and the boats go by on the Nile, before a nice local meal and bed.

Tuesday morning I was lying in bed when I heard a very familiar sound — the whoosh of hot air balloons. It’s amazing how that sound immediately transported me back to Melbourne, where we used to hear them drifting over our house many morning. I opened the curtains and they made a spectacular view hanging above the rice and banana fields with the moon in the background.

Next up was the Temple of Luxor. When you get off the ferry, there’s a remarkable lack of directions as to where the entrance is. Google isn’t a great deal of help either — it lists the physical location but not the entrance or ticket office. This is a roundabout way of me excusing our clueless wanderings that ended up with us walking to the entrance by going around the Avenue of Sphinxes. Now that doesn’t sound TOO bad, until you realise that the Avenue of Sphinxes stretches for 3kms between Karnak and Luxor temples. Fortunately after around 1km there is a bridge that brings you back to the other side of the Avenue! I suspect a few horse and cart drivers were trying to tell us we were going the wrong way, but we ignored them in our stubbornness and persisted in “walking like an Egyptian”, which was a common comment when we told people we’d prefer to walk and see the sites.

The Temple of Luxor was constructed in around 1400 BCE and was dedicated to “the rejuvenation of kingship”. It’s speculated that many of the pharaohs of Egypt were crowned here (or in the case of Alexander the Great, claimed to be crowned here, although he never actually travelled this far up the Nile). A section of the template was converted to a church by the Romans in 395AD and then later to a mosque in 640AD which makes this the oldest continually operating building in the world — it’s been an active site of worship for over 3,400 years…

After a walking through the markets for lunch (freshly cooked bread and freshly squeezed orange juice), we then bartered for a motor boat to take us up river to the temple of Karnak. It seems that this is not actually a common thing to do as there’s no real dock there — we were dropped off on the side of the Nile and had to leap across the mud, clamber up the embankment and then “turn left and you will see the temple”.

Although as a general rule, we tend to brush off local touts — every now and then they are persistent; amusing or just cheap enough that we succumb. We took the horse and carriage the 500 meters along the embankment to the entrance. The driver ruined the experience a little as he turned to me with a knowing wink, glanced at Karina and said so only I could hear “lovely jubblies” referring of course to her breasts. This was an unfortunate (although at times amusing) trend where the men would make rather directed comments to me that Karina wouldn’t always hear. I was frequently told “you are lucky man” to which I can only agree is true, but still it would be nice if they kept their opinion to themselves at times! Even when they speak Arabic, I know enough of the cadence to get a sense of what’s being talked about, or phrases like “hubba hubba” appear in the middle of a sentence as we’re walking past give it away.

Karnak Temple (started around 2000 BCE) deserves its title as the second most visited place in Egypt after Giza. Approximately 30 different Pharaohs contributed to its development which took place over a period of 2,000 years or so with each Pharaoh adding, subtracting, rearranging and modifying the prior parts.

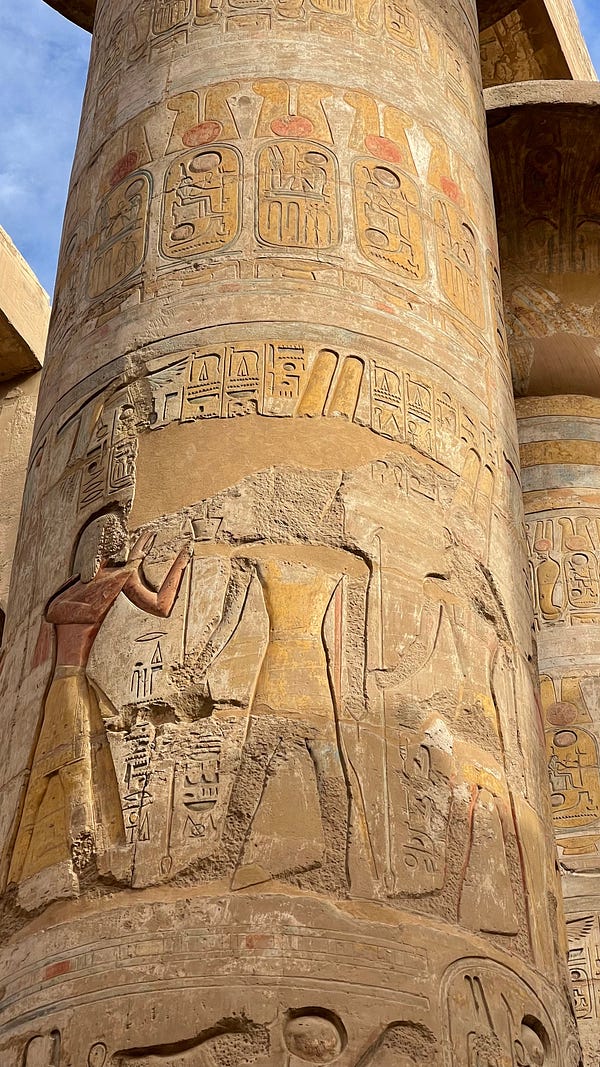

It covers four main parts, but the one that’s most open and visited by tourists is the Temple of Amun-Ra. It contained what were at the time the two tallest obelisks ever constructed and my favourite part, the great hypostyle hall which is made up of 134 columns in 16 rows, the middle two rows made of columns 24 meters high and 10 meters in circumference. The hypostyle hall covers 5,000 square meters in size. To put that in perspective, the precinct of Amun-Ra, which contained the temple is around 250,000m2 (or around 47 standard sized soccer / football fields).

It’s about now you start to stop and think “but why”? Between the tombs, the mortuary temples and the other places of worship, it all represents a significant investment on the part of the Pharaohs, using significant resources of the country. Although Egypt was described in antiquity has having gold that was “as common as soil” according to a quote I saw in the Luxor Museum, the amount used and wasted in death was mind boggling. Tutankhamen was buried in a gold coffin of 132kgs of pure gold while the walls of his tomb were lined with gold leaf — and his tomb was TINY and his reign incredibly short compared to many other much more powerful Pharaohs. That’s a lot of wealth to be sticking in the ground.

The answer to “why” is of course, religion. We’ll come back to this, but while we’re on the subject of Karnak, keep in mind that an estimated 80,000 servants and slaves were in service to the temple of Amun-Ra at the height of it’s power roughly 1,500 BCE.

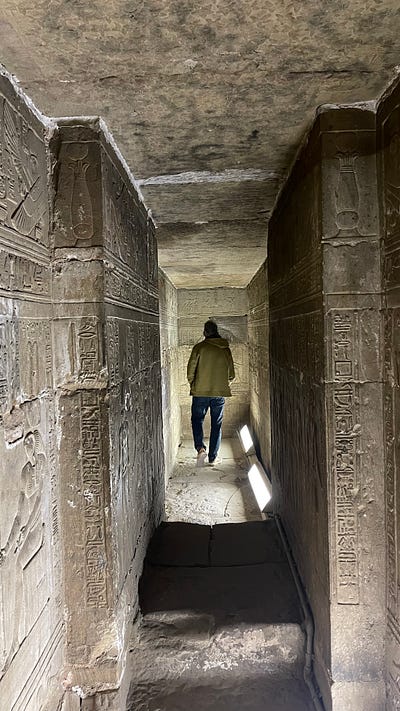

Wednesday we decided to tour the West Bank, the site of most of the ancient ruins but in particular, the Valley of the Kings which contains 62 known tombs of predominately Pharaohs, including notably Tutankhamen and Seti I.

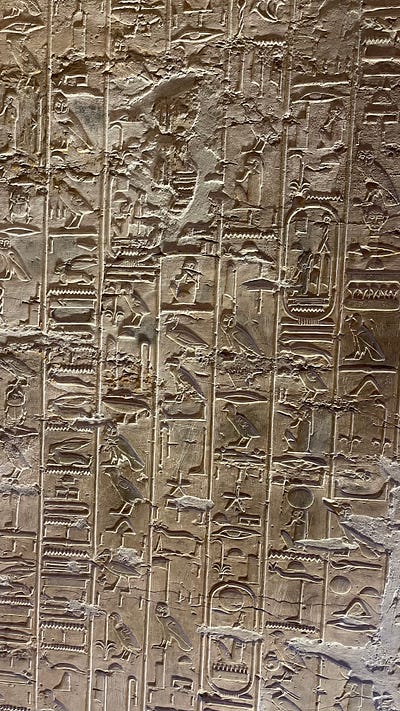

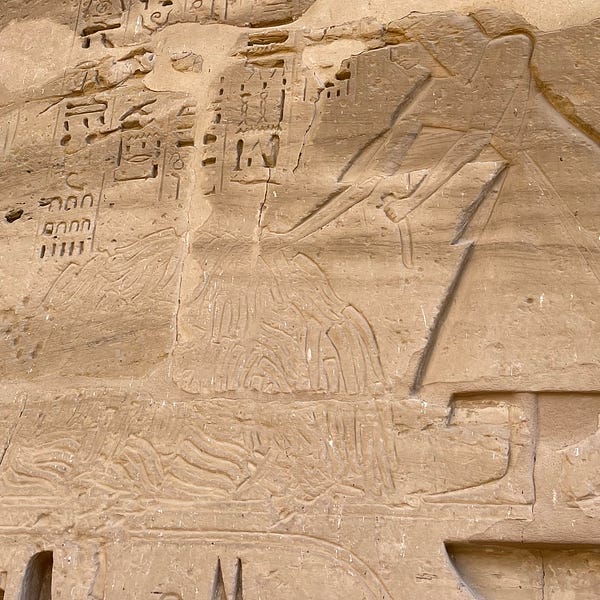

The tombs go through several different artistic styles — initially very plain, then painted, then carved, getting increasingly get more ornate — peaking with Seti I who had the most amazing tomb with hieroglyphics carved in relief. Then later, more brutal, deeply etched carvings in the walls. The delicacy is gone. Why this change?

Jealousy and power.

You quickly start to recognise a large degree of repetition in the art. The moment for me that really clicked is realising that they are all telling a variant of the same story. Imagine going to five churches one after the other — you’re going to see similar themes and stories being told. The 12 stations of the cross, Jesus on the cross, the Virgin Mary (especially in Catholic Churches), candles being burnt, a stand up the front… the implementation will vary, but the themes remain constant. The same is true for the ancient Egyptians. There’s a story being told, that unfolds in a similar way on the wall of each tomb, drawing from the same source material — the “Egyptian Book of the Dead”.

The difference from (most) modern religions is that the Pharaoh is a God on earth, a direct intermediary between the Gods and the people. At least initially, it was only the Pharaohs that could be resurrected again and experience life after death (although I believe in later years it extended to the idea that everyone could do this). But there was a careful process that needed to be followed, including mummification to prepare the body for this crossing over and to ensure that the soul could find its way back to the body again later. A lot of this process also involved careful decoration of the tombs with detailed instructions, advice and spells that invoked the godliness of the Pharaoh in question, strewn with liberal mentions of said Pharaohs name in his cartouche.

But what’s this got to do with art? Why would the style change and become more deeply etched… Well I’m glad you asked!

The pool of people that a God on earth can marry is pretty slim pickings — to preserve the symbolism of being a living god, you need to marry another descendant of a God, which means you end up with Pharaohs marrying their own mothers, sisters or daughters. Besides some gnarly genetic side effects, this kind of familial relationship creates complex family trees and somewhat arbitrary inheritances. No one can really hate you like the brother from your own sister that’s also your nephew.

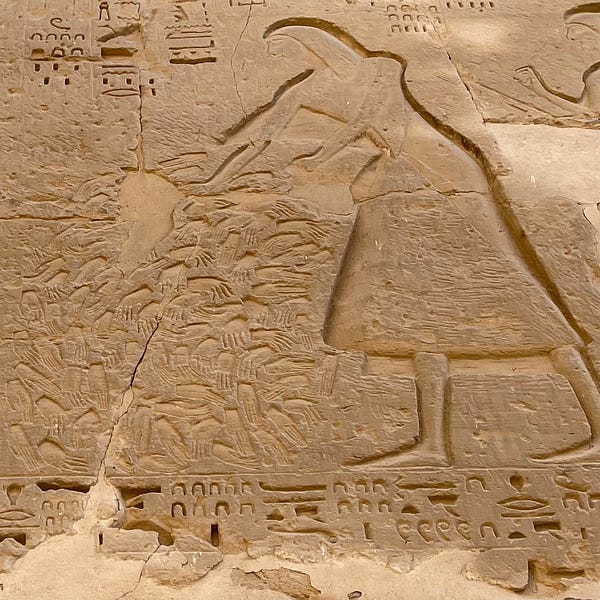

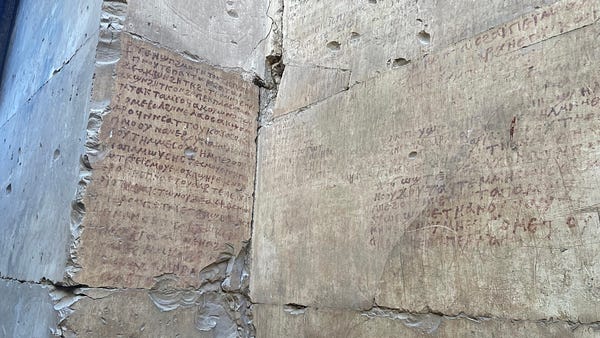

If weird cousin-brother-nephew Teti suddenly dies early (or was murdered) leaving you with a clear run at the throne, it turns out one of the first things you do is wipe their names from the records, especially if either a) you didn’t like them much or b) you want to acquire their glory for yourself. Tomb after tomb, temple after temple a recurring theme is vandalism.

Sometimes it’s the petty kind of “Tim was here” type that plagues civilisation everywhere — although in the 18C, it did take a bit more effort to carve your name into stone instead of whipping out the magic markers. But with the Pharaohs it was a detailed program of removing all references to the preceding Pharaoh and replacing it with your own. While it was sometimes “malicious”, it might also have been done pragmatically — Teti passed early and his tomb was unfinished — I’m going to take over his tomb and redo my name in the bits completed and extend it to make me something really grand.

Or, in the case of poor young Tutankhamen, you just die too young, so they quickly empty out a tomb of a priest, slap some paint on the walls and call it a day. Even the mask of Tutankhamen is (probably) that of an earlier pharaoh that was altered — they took one that was completed, covered over earring holes with gold leaf and changed a few features. The famous golden visage of the boy king is (possibly — this is still contentious) based on a mask of queen Nefertiti.

Which brings me back to carving your name in a wall.

The reason according to our guide that later Pharaohs go for a more brutalist style of carving with deep etchings is purely pragmatic. It makes your name harder to erase.

Back to the tourism — I highly recommend Valley of the Kings. Like us, you’ll probably do Tutankhamen’s tomb, it’s not worth it, but you feel like you “have to”, it’s the really famous one. It’s also the least impressive by far. You do get to view his mummy which is kind of trippy. All of the tombs are spectacular, but it’s Seti I that stands above for me for its intricate raised reliefs. Unfortunately the volume of tourists is causing damage to the atmosphere in the tombs and the paintings on the walls. One way they are trying to limit this is to increase the cost of certain tombs to discourage lots of people visiting.

After Valley of the Kings we visited the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut which was impressive, until you realise that it’s 90% reconstruction including using a lot of stone from a neighbouring temple. There’s a balance between restoring, preserving and reconstructing to allow people to get a sense of what was there — this one goes too far in my view — a lot of it is not original and when you see original photos compared to what’s there now you realise just how much has been recreated.

Next we visited saw the workers tombs Died-el-Medina, an interesting contrast to the grandeur of the kings, to instead see the more humble tombs of the workers who built them. Finally we visited the Mortuary Temple of Rameses III.

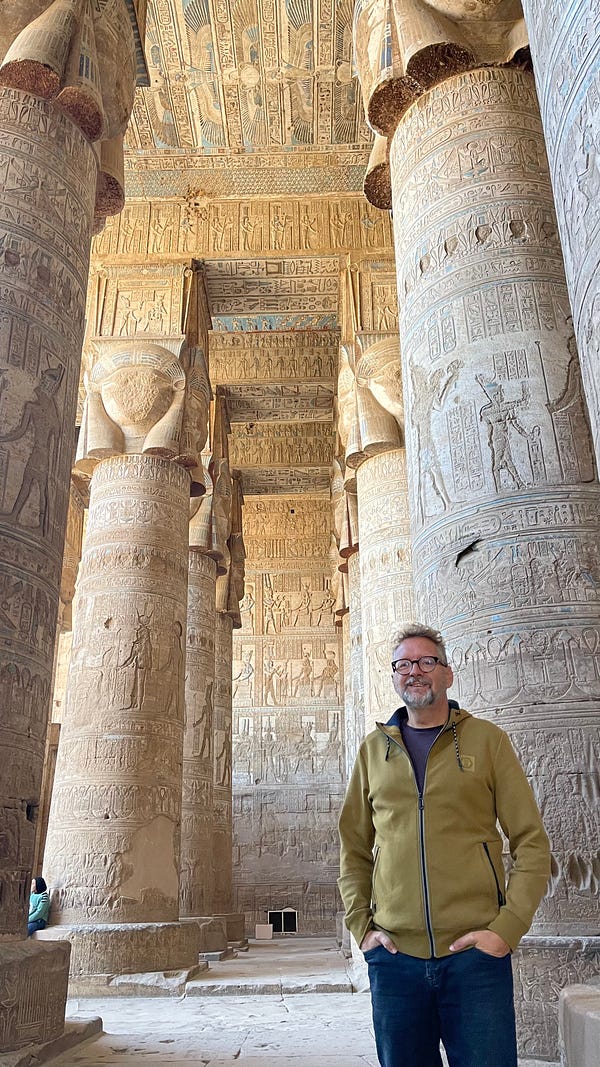

Thursday we headed to what was probably my favourite of all the temples we saw, Dendara Temple and then Abydos Temple, a few hours away from Luxor by car.

Dendara has held religious significance back into pre-history but the first concrete evidence for temples being built starts around 2250BCE. Today the earliest standing building dates to Nectanabo II (the last ‘native’ Pharaoh) in 360BCE, but the dominant and most spectacular building on the site is the Temple of Hathor, which is considered the best preserved temple complex in Egypt. The roof is almost completely intact and as a tourist you can access the crypts, walk the stairs to the roof and explore the top as well. It’s an amazing experience.

It also is one of the best illustrations of power-in-action that you’ll see.

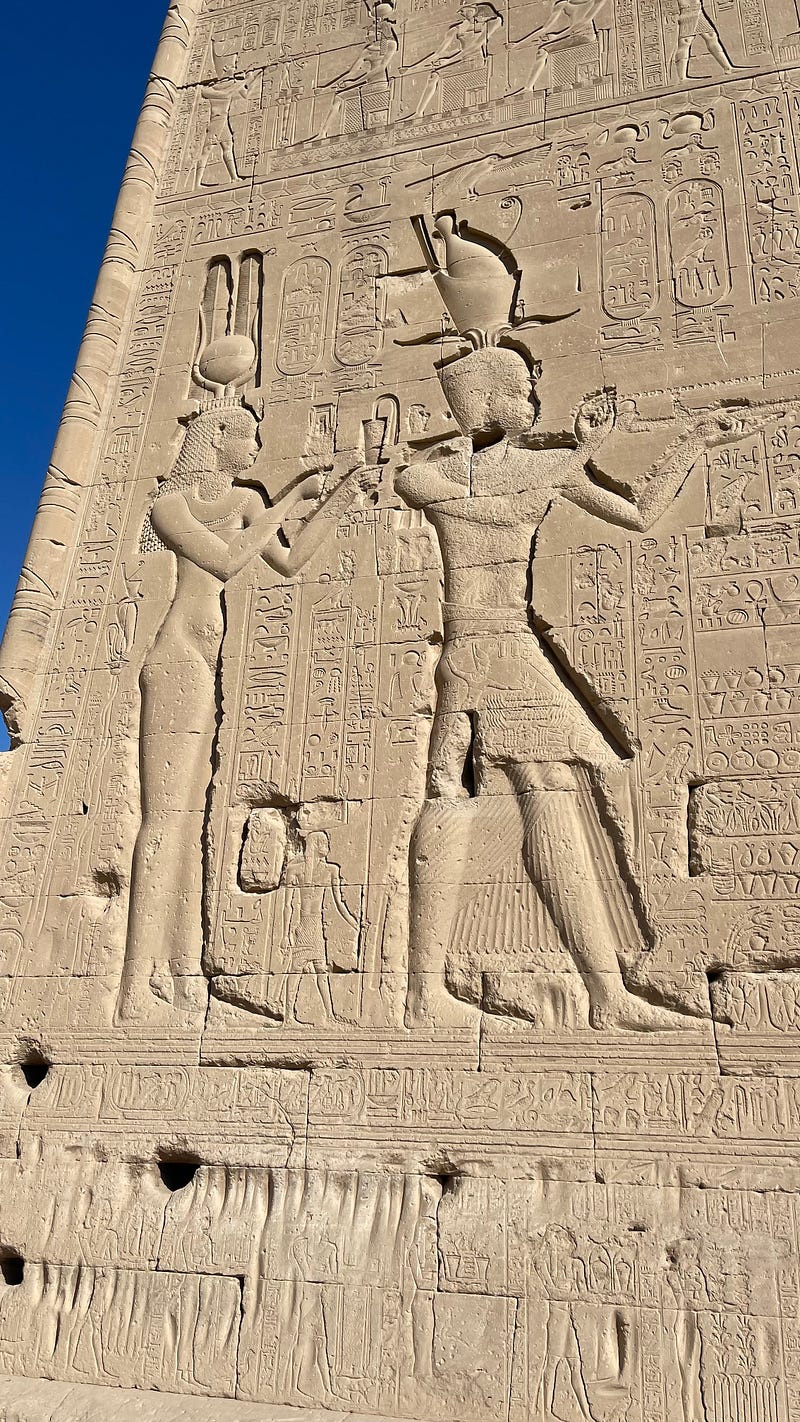

It feels like an ancient Egyptian temple from the Middle Kingdom (and some parts are), yet many parts of it are built in 150AD. You see the same stylised images as in other temples and tombs — Pharaohs being standing with the gods, receiving the key to eternal life but when you read up on it, you learn that this image, repeated everywhere through the complex is in fact the Roman Emperor Trajan.

I mentioned at the beginning that Cleopatra VII (yes the famous one from the movies), was the last of the Pharaohs, so what’s going on here? Basically Ancient Egypt was in decline and in 343BC, Nectanabo (the last native Pharaoh) was defeated by Alexander the Great (i.e. the Greeks). Alexander declared himself Pharaoh and ruler of Egypt and (presumably) with some liberal donations to the priesthood had an oracle declare him a descendant of the Gods. He then buggers off and gets himself killed crossing the alps. He left behind several generals, and eventually one of them Ptolemy I Sotor, emerges victorious in a bloody war for power and starts the Ptolemeiac Dynasty in Egypt — a period of around 300 years where Egypt continued as an independent state under Greece, with Greek rulers who considered themselves Greek, but stylised themselves as Pharaohs in order to keep the priests happy, prove their divinity and through the priests, keep the local population under control.

Eventually Egypt, like Greece becomes a vassal state of Rome. Cleopatra VII — a direct descendant of Ptolemy I Sotor — gets embroiled in the roman affairs, first as a lover to Julius Caesar, bearing him a son, Caesarion. After his death, she becomes lover (and possibly wife) to Mark Antony, including lending her navy to his cause in the Civil War between Mark Antony and Octavian, where the battle is soundly lost, Marc Antony is captured and killed and she famously commits suicide instead of being dragged back to Rome. At this point, that’s it for the Pharaohs. Egypt is now under the direct control of Rome.

But it’s not it for the religion.

The Roman Emperors weren’t generally idiots and Egypt had an incredibly important role as the breadbasket of the Empire. Keeping the populace quiet, happy and the grain flowing was important for life back at home.

So the tradition of deifying the rulers continued. Money flowed to the priests and the temples, who iconified the rulers, presenting a veneer of legitimacy and keeping the populace under control. Despite the fact he probably never did more than visit (and I’m not sure he even did that), Trajan and other rulers are immortalised as Pharaohs, incorporated into the religious life of the local Egyptians.

This combination of relative youth of the construction and place in the desert has kept the Dendara complex remarkably well preserved. They are in the process of restoring it which largely involves gradually removing the black soot from torches which built up over generations previously to expose the vibrant colours, but structurally it’s very intact.

On to Abydos which at this point now has blurred into yet another of the many temples we visited, but of particular note — a traditional Egyptian breakfast with our driver Mahmoud, then a visit to the temple where we saw early Phoenician graffiti, more church graffiti, an enthusiastic tourist guard who followed us everywhere while handling his machine pistol while swinging it around in the air and what was probably my favourite scam I experienced here in Egypt.

It’s ridiculously simple. “Can you change 5 euros for me?”, asked the desperately poor looking man with his 3 year old son at his side. If you’ve ever travelled, you’ll know that for whatever reason, you can’t change coins at the bank. My gut instinct was “No”, as I didn’t have any Euros on me at the time, but then I thought — I guess I could just give him the Egyptian Pound amount. A quick search online and 5 Euros is currently 88 EGP. Of course I only have a 100 EGP note, but at this point, I’m well along here so I just give it to him and pocket the 5 Euros in coins. I walk away feeling good and then about 30 seconds later realise it’s a very slick scam.

Tips from Europeans in Euros is not uncommon, so I’m sure that he knows the value quite well — if I’d offered 70 EGP, he’d of turned it down, but he’s very happy to take the rounding up, and in fact expects it. Chatting with Mahmoud later, he says this is indeed a common scam here — but in Luxor, you’ll typically find that a few of those Euro coins are suddenly Egyptian Pound coins making it even more profitable. Anyway, respect! I felt good, he felt good — you have to appreciate that.

Friday, after several early mornings, we took things slow — slept in, enjoyed the apartment, the sunshine and the views, then headed in to Luxor across the river to organise a PCR test in preparation for our flights back to Athens. A walk through the markets, a visit to the mummification museum and then it was home for a quiet afternoon.

Saturday morning is of course Christmas Day — an unusual one as it’s not celebrated here at all. We chatted with family, then headed in to the Luxor Museum, back home for a rest and then the Howard Carter House. The Howard Carter House was a nice change of pace, seeing something a little more modern and exploring the articles and information about the man who uncovered Tutankhamen’s tomb.

On the way back to town we spotted Mahmoud at a cafe, so we headed over to say hi and we were greeted with great delight. We all sat down and enjoyed a coffee and tea together, chatting about crazy tourists, Egypt and life in general, while watching the world go by from the middle of a two lane road as the seats were actually on the traffic island. Such is life in Egypt.

Finally Saturday evening, we headed to a local cafe that was offering a Christmas Dinner, complete with turkey, plum pudding and mince pies. It was a fun experience enjoying some traditional comfort food, sitting outside in an Egyptian Cafe looking across the River Nile.

Well, that’s pretty much it for this week — apologies if I get a little heavy on the history here, in some ways I didn’t go as deep as I wanted, but I suspect it was more than deep enough. It’s a fascinating country and we have loved Luxor in particular, we definitely feel like we could spend a lot more time here. The people are friendly, the river is spectacular and the weather is great, along with an endless supply of ruins to visit and experience.

Merry Christmas to all,

Until next time,

Tim and Karina