Week 130 - Exploring Bosnia & Herzegovina

Exploring Bosnia & Herzegovina

Driving in Rada the Lada through BiH, Mosta, Sarajevo and into Croatia.

It’s hard to capture just how amazing we’ve found Bosnia & Herzegovina (I’ll use the local abbreviation of BiH from here) to be. It’s such a dramatic country. Dramatic landscapes, dramatic history, dramatic architecture… it’s just all around dramatic.

Winston Churchill famously didn’t say “The Balkans produce more history than they can consume.” For the curious, this is a misattribution, the original quote was “the people of Crete unfortunately make more history than they can consume locally” by Hector Hugh Munroe, 1911 in his book Chronicles of Clovis. Nonetheless, it has stuck around as a saying because frankly it fits just too well, and Winston Churchill is of course one of the worlds great orators.

With that in mind, sit down and buckle up because we’re going on a ride. Endless scholars have written, debated, analysed and spoken about the history here — I shall do my best to summarise it into something coherent and digestible. Fair warning, I’ll get much of it wrong, and I’ll say things that are controversial and definitely over simplified but I hope it helps piece things together anyway.

The history of BiH is a country that has long been defined by foreign rulers. Like the rest of the Balkans there is a rich history going back to Neolithic times, but the first references to Bosnia as an independent entity date to the 12th Century when the Banate of Bosnia existed which eventually formed into the Kingdom of Bosnia. Although it was considered part of the Hungarian empire by Hungarian kings, there is no evidence they had any influence at this time and the Bosnian Kings ruled independently. In the 12C the religion was “Bosnian” christian, a form of christianity deemed heretical by both the Orthodox and Catholic christians. It was gradually suppressed and by the time BiH was annexed into the Ottoman empire in the 15C it no longer existed. Overtime, many Bosniaks converted to become Muslim.

It’s important background because as a local put it to us in Sarajevo “You see a horrible war, and it was horrible, but for us, it’s important and a cause for celebration as it’s the first time we stood up for ourselves and fought for our right to be free.”

When talking about BiH, there’s a few basic facts which are worth keeping in mind — it’s part of why understanding all of the events here is a challenge. If you keep the following in mind about modern BiH, it will help as we get into the detail.

- It’s two independent states — The Republik of Bosnia & Herzegovina (predominately Muslim) and The Republik of Srbska (predominately Serb), ruled as one nation, BiH. Think of this as something like Scotland, England, Wales and Northern Island functioning as the UK. The Bosnian-Croats are generally in favour of adding a third, Croat majority state to the federation although this has not happened yet.

- Croats, Bosniaks and Serbs as terms can be confusing — I’ve often made the assumption that “Serbs” refers to Serbians, but this isn’t technically correct. Serbs as an example refers to an ethnic group (a people with a shared cultural background and heritage) that exist throughout Serbia, Montenegro and BiH as well as elsewhere. There are Bosnian-Serbs, Bosnian-Croats etc. What many (but not all) Bosnians will tell you is that really they are the same people (and genetically this is correct), but they “just” have a different religion. The vast majority of Serbs are Orthodox, the vast majority of Croats are Roman Catholic and the vast majority of Bosniaks are Muslim. The confusion I’ve faced at times is that when someone says “The Serbs” did this, they don’t mean the Serbians (although Serbia was supporting Bosnian-Serbs), rather they mean that Bosnian Serbs did this. Collectively all these groups are known as the southern Slavs and they’ve been here since around the 6C BC.

- Keeping this all in mind, it’s easier to understand that what starts somewhat as a war for independence quickly descends into a civil war between factions with different perspectives on independence (or more specifically HOW they want to be independent post the fall of Yugoslavia). Into this mix is added 100+ years of grievances fuelling the problems. Indeed, what we in the US, UK and Australia sometimes think of as “The Balkans War” is really a series of smaller wars.

- It’s also useful to understand that Yugoslavia, literally “Land of the southern slavs” was always a series of independent kingdoms and regions — Slovenia, Croatia, BiH, Serbia, Montenegro and Macedonia which each to one degree or another had their own historical kings and countries. The success of Yugoslavia can be broadly attributed to the sheer force of will of Josip Tito, the communist partisan leader who rose to lead it and hold it all together. After Tito died, things gradually started to fall apart and accelerated with the collapse of communism in 1990 with Slovenia declaring independence in 1991 followed shortly by Croatia.

- Finally, there’s acronym overload. The JNA, HV, HVO, VRS and ARBiH are all combatants at various times and there are several phases of combat across several years with different parties both allying and opposing each other. We’ll touch on these as we discuss some of the historical events.

Enough background for the moment! Moving on to the journey, we set off in Rada the Lada on Monday to head up through the mountains of Montenegro to BiH. As with our drive to Bulgaria late last year, it highlighted how isolated and separate these countries really are from each other geographically. While trade routes existed, it also wasn’t easy to move from one place to another — a short geographic distance could be impassable, especially in winter.

Eventually arriving in Mostar after a very pleasant drive, we were greeted by our Airbnb host whose second sentence after “Hello I am Armela” was “Let me tell you about the siege of Mostar.” This came as a surprise. We weren’t exactly sure what we’d learn about this period while we were here, but for reasons that become obvious, we learnt a lot. Certainly we found Bosnians to be a lot more open and willing to talk about that period than Montenegrins, for reasons which perhaps start to make sense as we unpick things a little.

It was clear driving into BiH that there isn’t much obvious tension nowadays between Montenegro and its neighbour. The border crossing was very straightforward and the security guards were literally sitting in the same check point hut, facing each other across the table. The Montenegrin guard stamped our passports and then just passed them over the desk to the Bosnians who stamped us in and away we went while they bantered back and forth.

As we walked with our host from the car park to the Airbnb about 300 meters away in the old town she gave us a run down on which buildings had been destroyed during the siege of Mostar.

“Why do you think this cemetery is in the middle of town?” she asked and then proceeded to answer her own question. “During the siege it was terrible, many people were starving and we needed somewhere to bury the dead. This used to be a park, now it is kept as a graveyard memorial to those who died.” It’s an eerie experience, one we’ve since had repeated time and time again here walking past tomb stone after tomb stone with a date of death listed as 1993.

She then pointed out a derelict building “After the siege, 70% of the buildings in town looked like this. Many, including this one, still haven’t been restored.”

It’s an ever present scar as you walk around the town; that something terrible happened. While many buildings are now fully repaired, there are shrapnel marks frequently still visible and plenty of derelict buildings although fewer every year. Some derelict houses have notices on the door telling the story of the resident and the fact that they still haven’t been able to raise money for the repairs, so it sits essentially abandoned, but not forgotten.

Mostar today is a delightful place to visit and a welcome break from the “typical” Venetian or Austro-Hungarian style architecture we’ve come to associate with old towns here in this region. That’s because it has continued as a predominately Muslim community (at least in the tourist part of the old town) and still retains a lot of that Moorish style. It feels different which is a refreshing change.

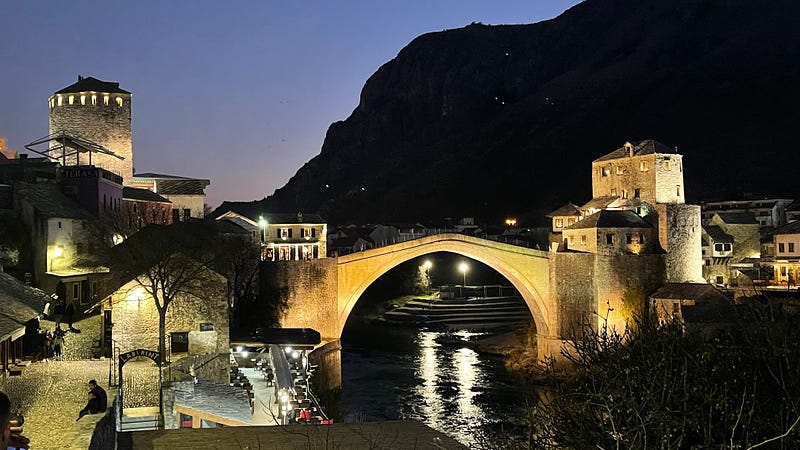

We wandered the old town, over the UNESCO listed old bridge of Mostar (completed 1566, destroyed 1993 and rebuilt 2004) which links the two sides of the city across the river Neretva. At its completion in 1566 it was the widest man made arch in the world. It’s this bridge that gives the city it’s name — Mostar comes from mostari, or bridge-keepers. We climbed one of the towers overlooking the bridge and experienced our first Bosnian coffee with a stunning backdrop overlooking the river. The old town is full of restaurants, many converted from old water mills. Today it features on the Red Bull Cliff diving circuit as people dive from the bridge into the cold waters of the Neretva below.

Mostar was besieged twice, but to tell that story and understand why, we need to jump back in time. Sorry if you thought I was done with the history! I’ll cover some more of this when we get to Sarajevo, but for now what’s important is to understand that Serbs and Croats were on different sides during the World Wars, with Serbs (what is now mostly Serbia) trying to stay as a neutral monarchy and Croats willingly allying with the fascists (Germans / Italians). The Bosniaks have always been a bit “in the middle” here, but generally have allied with the Croats and did so during WWII.

During WWII the Croatians were lead by the Uštase — a very nasty piece of work, so vile that even the German SS considered their methods extreme. Under their direction, the Croatians, along with their Bosniak allies terrorised Serbs killing hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, Roma and Croatian political opponents. There is a long history of hatred and horrific behaviour on both sides here which never excuses genocide but may help you understand the depths of feelings Serbs and Croats have towards each other.

After the fall of Yugoslavia, Slovenia and Croatia successfully became independent (which is glossing over the Croatian War of Independence), but when it came to BiH, there was a mix of opinions. BiH contained a lot of Serbs who started declaring “Serbian Autonomous Regions”, were supported by Serbia (essentially the backbone of the remaining Yugoslavia) and they armed themselves using the resources of the Yugoslavian National Army, the JNA. By March 1991, the JNA had distributed an estimated 51,900 firearms to Serb paramilitaries. In response the Croatian Government began arming Croats in Herzegovina as well as Bosniaks.

Because the JNA had tried to prevent the Croatians becoming independent, local Bosnian Croats viewed them as a hostile occupying force and tensions increased in the area as BiH moved towards declaring its own independence.

The Croatian Army (HV) clashed with the JNA in towns surrounding Mostar and formed the local Bosnian Croats into militias called the HVO. Having declared independence, Bosnia formed the ARBiH (Army of the Republic of BiH) which contained predominately Bosniaks, but also some Serbs and Croats loyal to the idea of BiH.

War then breaks out and the JNA lays siege to Mostar in April 1992 as well as Dubrovnik and Sarajevo amongst other places. The JNA is consisting at this point of predominately Bosnian Serbs mostly loyal to the idea of Yugoslavia.

This first siege of Mostar is lifted after roughly three months when the Croatian Army (HV) and the Militias (HVO) successfully coordinate an attack that pushes the JNA back, lifting the siege. The Croatian army commander then relieves all Bosniaks from positions of power inside Mostar, putting local Croat politicians in place instead.

I said that Bosnians in general seem to be a lot more willing to talk about the wars than Montenegrins. I think that’s because they perceive themselves largely as the victims and Montenegro also wasn’t impacted much which at that point as it was still part of Yugoslavia. The Prime Minister of Montenegro did controversially apologise for their role in the siege of Dubrovnik and several guards were prosecuted for prisoner abuse in the war camp at Merinj (just near where we are in Tivat). In Montenegro, you’re more likely to hear of hostility towards NATO for bombing several targets to try force the former Yugoslavia to abandon its aggression in Bosnia and its support for the Bosnian Serbs. Surveys conducted in Serbia in the 2000’s showed only 20% of Serbian Serbs believe the JNA laid siege to Mostar at all.

Politics happen, Yugoslavia continues to collapse and the JNA in BiH is disbanded. In reality, it just renames itself the VRS (Army of the Repbulik Serpska) largely consisting of Bosnian Serbs and folding the militias in under its command. It’s still the JNA, just under a different name and command now localised to Bosnian Serbs, all former JNA officers.

Back to Mostar, for about twelve months things continue along, but relations between the Croats and Bozniaks deteriorate. Croatia wants an independent Bosnian Croatian state, while the Bosnians won’t agree. Muslims are ejected from the HVO, Croats ejected from the ARBiH and by April 1993 Mostar is divided with the HVO owning the west of the city and the ARBiH the east.

Stories are mixed about who kicked off what, but on the 9th of May 1993 both sides come under artillery attack from the other side. The HVO responds by ejecting all remaining Muslims from western Mostar and placing them into concentration camps where they are starved, tortured and some killed.

The VRS (formerly JNA), previously the aggressor, now finds that both combatants are neutral towards it — at least around Mostar. It plays both sides of the fence, trying to keep the conflict going by aiding both the ARBiH and the HVO depending on who has the upper hand at the time.

This continues until April 1994, for 11 months, until an agreement is brokered between the parties and the HVO withdraw from BiH. The siege resulted in the death of around 2,000 individuals, around 50% who were civilians. Mostar was the most heavily damaged city in BiH and from the start of the war where it was roughly evenly split in demographics is now largely dominated by Croats on the West bank and Bosniaks to the east. The city has remained so divided that it was not until July 2020 under international mediation that legislative amendments could be agreed to allow proper council elections to be held.

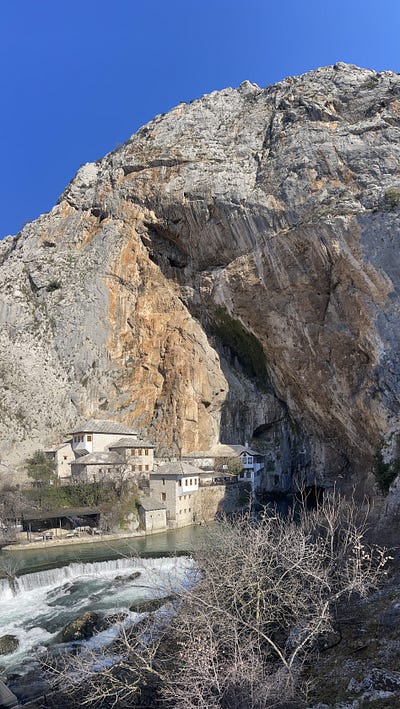

From Mostar we headed to visit the Monastery of the Whirling Dervishes, a stunning location under a large cliff that has to be seen to be believed. We then headed to Stolac and drove Rada off-road through some fairly extreme dirt tracks only to meet a large dump truck which refused to let us pass — it was dragging dirt up the hill in reverse to dump it to repair the road. So much for Google Maps.

We visited one of the many Necropolis sites that are scattered through BiH — these are generally old christian burial sites from the 12C-15C and not a great deal is known about them. One interesting piece of information is that the anchor symbol is typically a “hidden cross”. Then it was off to visit the old mill at Stolac, wander the streets under the castle then headed back to Mostar for the evening.

On Wednesday we headed to Sarajevo. It’s an amazing drive along a steeply sided valley, at the base of which runs the Neretva River. Half way up we stopped at Konjic to visit Tito’s bunker.

Tito is a polarising figure in the former Yugoslavian states. He’s both authoritarian and capricious, but at times a benevolent dictator. He’s a war hero and for 30+ years he managed the impossible of keeping the loose coalition of Slavic nations bound together in a united front.

As the tour guide said to us “I like giving tours to English guests, you have to be too careful what you say to the Slavs. It always ends up having to separate people from big arguments.”

With unemployment running high here, it seems that your memories of Tito’s rule really depend on your perspective — if you or your family were members of the communist party it was a guaranteed job, health care and everything looked after for you. Today seems tough. On the other hand, for many it was desperate times with people imprisoned for simply making jokes and essentially forced labour if you weren’t in a favoured position.

At the end of World War II the allies, lead mainly by the United States gave a large sum of money to the new Yugoslavia to help it rebuild, which Tito directed into military vanity projects, namely his bunker, an underground airfield in the north of BiH and a naval base on an island off the coast of Croatia.

The bunker was built in such secrecy that it wasn’t until 2000 that the local populace knew of its existence. The very small number of guards (17) were sworn to secrecy and were all members of the communist party, while the workers who built it only ever worked on small sections and were bussed in, blindfolded from some distance. It cost around 4.5 Billion dollars to build, around 20 Billion today.

Despite the money, it had a series of design flaws so it’s probably a good thing it was never used! The big issues were that it was designed to withstand a nuclear attack, with 10 meter thick concrete walls buried 200 meters under a mountain, yet the people there could only live for 6 months before they’d have to leave — not enough time to survive the fallout. There was also the issue that the bunker was so remote that the people to be saved wouldn’t be able to get to it in any kind of useful time. It was an amazing tour of a piece of history you don’t typically get to experience and is well worth the visit.

When you arrive, there’s three plain buildings on the surface — they look a little like farm houses or perhaps administrative buildings for the nearby munitions factory (part of the cover that kept the area secret). Nothing to indicate whats hidden beneath the mountain.

My favourite part of the story is what they did with the stone. It was all excavated and then donated to the local town of Konjic which grew significantly during the 20+ years of construction. If anyone wondered why they were suddenly the favoured of Tito and where all this amazing new building material was coming from, they never decided to ask — a sound policy in those days. The school, town hall and many buildings in Konjic are made from this bunker stone.

The bunker was ordered to be destroyed by the JNA commander when they retreated during the wars, but two soldiers refused, instead unhooking the remote detonation system before flying away with the rest of the troops by helicopter. The ARBiH took over and in the mid-2000’s deemed it had no military use and instead would best serve as a museum.

From here we headed to Sarajevo and after settling into our apartment wandered through the old town a bit and then collapsed into bed.

Thursday morning we kicked off the day with a walking tour. This was an excellent introduction to the city and well worth the time.

The war is a bottle neck on history. It’s hard to think about Sarajevo without thinking about the war. If I was pressed, I think the only other thing I really knew was that this was where “the assassination of archduke Franz Ferdinand occurred that lead to World War I” but I couldn’t have told you much more than that.

The walking tour gave us a much broader introduction to the history of Sarjevo and its stunning old town. Historically, it was a trading city and the markets were reminiscent of the souks we’ve experienced in Arabic countries — streets and neighbourhoods dedicated to one craft. Today, there’s only one left that still functions the same way (the Coppersmith Street), but most of the streets in the old town still bear the names of the craftsmen who worked there. Locksmith street, Tailor street, Blacksmith Street, Gold Street and so on.

The Ottomans generally nowadays have a bad rap — after all every one was chafing at the bit to throw off the yoke. My suspicion is this has a lot to do with the decline of the empire in the later years and rampant corruption. But we have visited many cities where the early Ottoman administrators were both benevolent towards all religions and invested in significant architecture and facilities.

When the Jews were expelled from Spain, they were eventually welcomed into Sarajevo and it’s one of the few cities with Orthodox, Catholic, Muslim and Jewish centres of worship all close to each other.

The most famous of these administrators was Gazi Huzrev-Beg who built covered markets, new mosques and by endowment after this death, the Tašlihan, an inn for the caravans who moved through Sarajevo. The Tašlihan had 30 rooms where traders could stay inside the city for up to three nights before they were required to pay.

On his death Gazi Huzrev-Beg left his estate to the city and a madras was built in his honour that still operates today, although in a different building (the original is still there, but it’s now used for something else).

As the Ottoman empire declined, the “Great Powers” got together and in 1878 as part of the congress of Berlin, the Austro-Hungarian empire was granted the rights to administer Bosnia for 30 years, although it would still “technically” belong to the Ottoman empire. During this time they invested a lot of money into improving the city of Sarajevo, building the first electrified tram lines in Europe, electrifying the Gazi Huzrev-Beg mosque (the first electrified mosque in the world) and using the city as a “test case” for ideas to implement in the capital of Vienna.

The Austro-Hungarians also continued the policy of being neutral towards religions — when they needed a brewery, they didn’t discriminate, it was dropped in between a mosque and a church.

Today that development is still visible in the city where there is a distinct break between the old Ottoman architecture and the newer Austro-Hungarian city. Look one way down the street and you might be in Istanbul, the other and you’re in Vienna. The Austro-Hungarians also built a lot of buildings in New Moorish style, to keep them true to the character of the old city.

In 1908, the Austro-Hungarians did not (surprise!) return control as promised, but annexed BiH officially as part of their empire. As you’ll know from our other travels, the Austro-Hungarians stretched down the coast beyond Montenegro and they also wanted to control inland Serbia which would connect them more directly to their existing empire.

As it was put to us, they were just looking for a reason to invade. Of course, Russia was strongly on the side of the Serbians and the Austro-Hungarians couldn’t invade without a strong cassus belli. In 1914 when Gavrilo Princep assassinated archduke Ferdinand they had the excuse they’d been looking for.

Gavrilo Princep was a member of the Young Bosnians, a group of Bosnian Serbs seeking freedom from the Austro-Hungarian empire and importantly wanting to form a nation that was a union of southern slavs (Yugoslavia just entered the chat). The Young Bosnians were backed by The Black Hand (cool names hey!), a secret Serbian military group also pro the idea of Yugoslavia and sewing dissent to destabilise their powerful Austro-Hungarian neighbours. That was enough for Austro-Hungary to launch a war against Serbia, Russia to pile on in and the rest as they say is history. World War I.

Today there’s a statue of Gavrilo Princep in his honour in the Republik Serbska part of BiH and he’s considered somewhat of a martyr to the cause of Bosnian independence amongst Bosnian Serbs. History is complicated! Although our Airbnb host in Mostar told us that people also say if Princep had not assassinated the archduke, at the rate improvements were happening under the Austro-Hungarians, Bosnia would be a powerhouse like Germany now. More realistically, the world was a powder keg and any small spark would have ignited the fight if that one had failed.

We stood on the spot where archduke Ferdinand (and his wife Sophie) were assassinated. An awkward moment in some respects — do you smile? Do you look sombre? I’m never quite sure what to feel about that. For the record I ended up smiling, but it’s more in excitement for being in a place with such history.

Then it was on to the war. No tour of Sarajevo is complete without examining it at least in part. You still see physical scars everywhere in the city. Maybe 1 in 5 buildings still has shrapnel scars on the outside. During the height of the conflict, the VRS (Bosnian Serb army that was formed from Serb Militias and the Yugoslavian army — the JNA) was dropping some 360+ shells a day. Sarajevo was besieged by the JNA then the VRS for 44 months. The longest siege in modern warfare. Almost 14,000 people died during the siege of which 5,434 were civilians. The ARBiH suffered 6,137 fatalities and the VRS 2,241. The hills surrounding Sarajevo have fields of white tombstones of people killed during the conflict.

The trigger was of course BiH’s referendum for independence. 63.4% of the population voted and 99.7% voted for independence, but Bosnian Serbs largely abstained from voting and favoured remaining with the former Yugoslavia. Various conflicts between the parties eventually lead to full scale civil war.

At the beginning of the conflict, the ARBiH was poorly prepared and equipped having been hastily put together and the better organised JNA and VRS units quickly over whelmed them around the country, particularly in the east, pushing them back into Sarajevo. The ARBiH held the line in Sarajevo and the JNA was never able to take the city, instead opting to shell it from afar.

These shell strikes still scar the city today, evident on many buildings and on the ground. When the strikes were repaired, they filled them with red resin and these became known as “Sarajevo Roses”, several of which are preserved as monuments today around the Catholic Church.

After the tour we took Rosie back to the apartment for a nap and we headed across the city to take the cable car up to the old Olympic bobsled track. The Winter Olympics were held in Sarajevo in 1984 and they are still prominantely featured in advertising and imagery around the city.

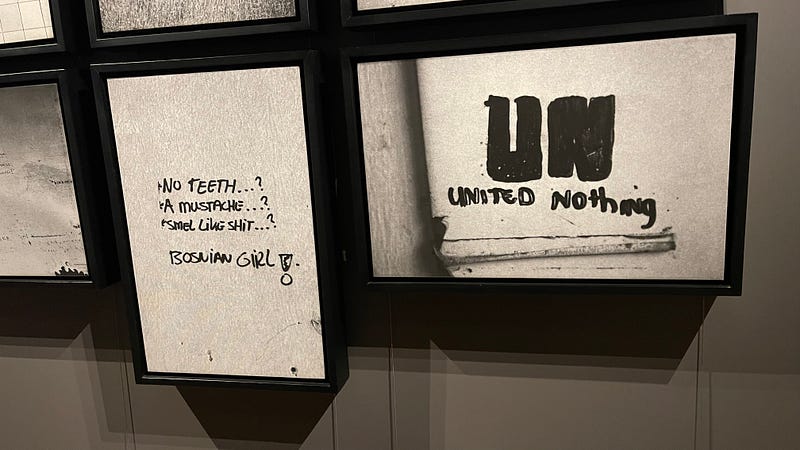

We also visited a photo exhibition on the genocide at Srebrenica, where over 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys were executed by the VRS under the command of Ratko Mladić. Around 30,000 Muslim women and children were forcibly relocated in a systematic ethnic cleansing. It was a sobering exhibit of just how fucked up this entire period of history was, with neighbour killing neighbour. And it wasn’t just Srebrenica.

Serb military, police and paramilitary forces attacked towns and villages and then, sometimes assisted by local Serb residents, applied what soon became their standard operating procedure: Bosniak houses and apartments were systematically ransacked or burned; civilians were rounded up, some beaten or killed; and men were separated from the women. Many of the men were forcibly removed to prison camps. The women were incarcerated in detention centres in extremely unhygienic conditions and suffered numerous severe abuses. Many were repeatedly raped. Survivors testified that Serb soldiers and police would visit the detention centres, select one or more women, take them out and rape them — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Sarajevo

It’s also a depressing tale on the ineffectiveness of the UN. In Srebrenica they were on the ground supposedly preventing conflict, but they were out gunned and unable to get any support to actually prevent the round up happening in front of them. They sheltered inside their base, turfed out the Muslims seeking shelter and then were there to count the bodies afterwards. The UN is NOT well regarded in the Balkans for many reasons, this is definitely one of them.

Although some Serbs continue to deny it was a genocide, there’s plenty of supporting evidence — much of it incredibly graphic. After the massacre victims were buried in primary, secondary and even tertiary mass graves as the perpetrators tried to hide the crime by moving the bodies from the primary to secondary locations. Tellingly the secondary and tertiary graves were often placed close to the front lines where the hope was they’d be mistaken as combatant victims of the war.

Our tour guide shared stories and spoke a lot about what happened, willing to answer our questions. What I found interesting was that before answering anything controversial, he’d look around — it seemed to me as if wanting to be sure just who would over hear what he had to say. There are still lots of tensions here.

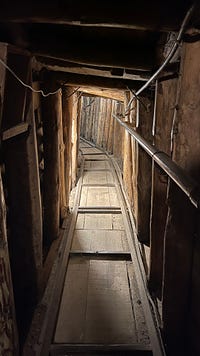

On Day 4 we hopped back into Rada and drove around Sarajevo to visit the War Tunnels. The tunnel was built under the airport (which was under Nato control) and was the only way in or out of the besieged city. Imagine a horseshoe — the airport was at the open end of the horseshoe and was “no go” land controlled by the UN. Inside the horseshoe was Sarajevo and the horseshoe itself was the ring of VRS forces. If you could get past the airport, a dangerous proposition across a kilometre of flat ground with sniper and machine gun fire from VRS positions, you could enter ARBiH controlled zone and escape the siege.

The ARBiH built the tunnel under the airport which allowed them to bring in supplies and people into and out of the besieged city. Daily between 3000–4000 people crossed through the tunnel as well as 30 tonnes of goods. It was an eerie thing to see, but also very interesting to visit.

With our fill of war related tourism now complete, we headed up to the “Yellow Bastion” below the old fort for coffee and a drink. We ate Bosnian cevaps for lunch and we took an afternoon off back at the apartment.

Saturday we drove out to the “Bosnian Pyramids” a natural formation which was a complete waste of time! The smog (which is renowned here) was so heavy you could hardly see them and we instead found ourselves driving through the countryside and exploring another abandoned Necropolis, although this one had nothing really remaining in it.

We came back into the old town to enjoy a walk through the streets again, had lunch at a local restaurant and toured a museum on the Austro-Hungarian period here. Then more Bosnian Coffee, the drinking of which is an art form in itself that requires plenty of practice and I also got a much needed haircut!

Tonight it’s a dinner in town then tomorrow (Sunday) we’re driving off to Split to spend a few days in Croatia.

To wrap up BiH — it’s been a fascinating experience. We were not really sure what to expect and it’s definitely somewhere I will recommend to people to visit in the future. I’m not sure we’ll come back again, we’ve enjoyed what we’ve explored, but we don’t feel a need to stay longer either.

I’ve been thinking a lot about a question from Viv Noot, which was “are the scars from the war starting to heal? To say ‘bad stuff happened’ feels inadequate.”

I don’t have a good answer although I will try. First I’ll leave you with two thoughts.

- The Bosnians I’ve met never want to forget what happened to them. How could they feel otherwise? Terrible things were done. But while they feel sorrow for what happened, both Bosniaks and Bosnian Serbs feel pride in their independence. They have their own territory and country and govern independently. The process has left deep scars that may never properly heal, but the outcome doesn’t seem to be regretted.

- I think scars have been papered over but in many ways, the country is more divided than ever. The concentrations of the ethnicities has changed and cities like Sarajevo and Mostar are more of a mono-culture than ever before. Sarajevo is mostly JUST muslims. East Sarajevo is mostly JUST Serbs. Towns that prior to the conflict had populations of around 60% Muslim in the Republik of Serpska are now as high as 95% Serb. Maybe this is a good thing (although not how it got there), people are ruled by people “like them”, but I can’t help but feel that it’s window dressing. People constantly complain about the dysfunction of their Government which is split into the three ethnic factions and apparently does not work well.

While I’ve felt very safe and welcomed here and I’d definitely encourage people to come, I’m also going to say that if tensions erupt and violence breaks out again in the future, I won’t be surprised. After all, there’s over 120+ years of tensions here now where terrible things have happened with a depressing regularity.

To directly answer Viv — “Yes, I think the scars are very slowly starting to heal, but the scars have also changed the face of the country and may lead to new complications later.”

For now though, it’s off to Croatia and the newest member of Schengen.

Until next time,

Tim & Karina